“Up a goddamn mountain: So that ignorant, thick-lipped evil whorehopping editor phones me up and says, ‘Does the word contract mean anything to you, Jerusalem?’”

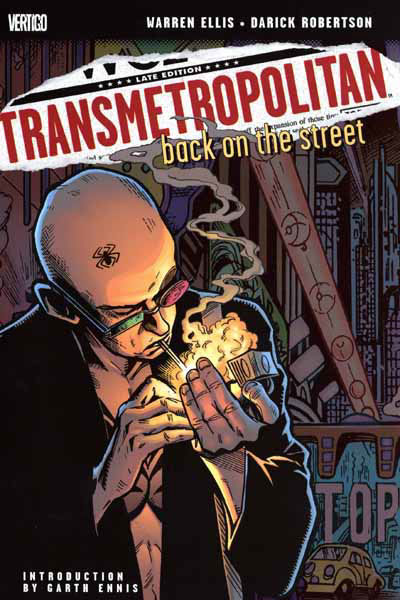

The first page gives you a pretty clear indication of what sort of story is about to follow. It’s going to be about writing. It’s going to be about a man who went up a mountain to get away from writing. It’s going to be a little, or a lot, crazy. And that’s only the text: check out the art, provided by master Darick Robertson. Just that first page. Spider’s wild hair, wilder tattoos, the disarray of his living space (there is a stack of cans, presumably beer, ascending to somewhere off-panel in the right corner), and of course the nudity. Judging by the bottle clutched in the hand not holding the phone, Spider isn’t just naked in a filthy mountain cabin, he’s also been drinking.

Yeah. The first page. It’s going to be a bumpy ride, friends.

What’s Going On

“Back on the Street” is short. It follows Spider Jerusalem down off the mountain he has retreated to, back into the City, which might be New York. Nobody seems quite sure. When he arrives, owing two books to the Whorehopper, he has no journalist’s insurance, nowhere to live and no money. So the first thing he does is assault the office of The Word in search of old comrade Mitchell Royce. Royce is now city editor. He gives Spider a columnist gig with provided living space and amenities. Of course, when Spider arrives there, it’s a dump and his Maker is on machine-drugs. The shower manages to burn off all of his hair from head to toe. (Now he looks like the guy on the cover.) His first story leads him to an acquaintance, Fred Christ, who has become a Transient. (An alien colony offered its genetics to gene-modifier cliques who have now become part-alien. It was their most exportable asset. These neither-human-nor-alien people are the Transients.) Fred has organized a secession of his poverty-stricken district to the alien colony without a whole lot of intent or intelligence. Spider warns him, “They’ll come in and stamp on your bones, Fred.” He ends up being right: a riot breaks out in Angels 8, the Transient sector. It was set up and paid for by non-Transient lawyers who Spider spied on his first trip in to interview Fred. By the time he makes it there, the police are raining down hell on the disorganized citizens. Spider makes it to the top of a strip-bar and calls Royce, offering to write the column he owes right then and there. Royce sells the rights to it to stream all over the city (without Spider’s knowledge). The column is straight-forward and brutal like the violence going on below. When the readers see it streamed over every channel, their public outcry forces the police to pull out before destroying the sector. Spider wins. Later, he’s attacked by police and beaten, but the closing panel is a bloodied, swollen-faced Spider yelling, “I’m here to stay! Shoot me and I’ll spit your goddamn bullets back in your face! I’m Spider Jerusalem and fuck all of you! Ha!”

The Part Where I Talk

To an initial reader, volume one might seem like a prologue. Introduce you to Spider and his ways through a nice short story about his first column back in the city. I’m going to try to avoid spoilers in these posts (try to play along if at all possible), but I’ll advise the new readers first and foremost: this isn’t a prologue. This is chapter one. This stuff? It’s important, so pay close attention. I just won’t tell you why. We can talk about that in the post for the last volume, right?

The most recognizable part of Transmetropolitan is of course Spider Jerusalem (the man, the legend). He has a way of talking that seduces a certain audience instantaneously. Mostly this audience will also be enamored with Hunter S. Thompson, who I don’t hesitate to say provided some inspiration for Mr. Jerusalem. (There is a panel in a later volume where there are some books on Spider’s table and one of them is by Thompson, so that isn’t simply weird conjecture.) Much like Thompson, Spider has a multi-faceted personality. It’s not just bad craziness, though that is part of the package. He is a man who loves the world so hard that it makes him hate. He’s the kind of guy who might put out a cigarette in someone’s eye, but he’ll also try like hell to save the lives (and eyes) of a hundred other people when they’re being victimized. That, above the drug-addicted lunatic hilarity, is what makes me come back for more. That’s the reason I’ve read this series once a year since I laid my hands on it, when I need to feel good or like there might be hope somewhere in the world. Spider is deeply complex and twisty in a way that perfectly contrasts the more over-the-top aspects of his persona: because that’s part of the game.

Which Spider is the real Spider—the one who, when he must return to the city and his public, is inherently depressed? The one who cascades into The Word’s office with a smoke grenade and a few well placed elbows? The one who Royce says turned in a column that said “fuck” eight thousand times? The one who slumps into a chair and admits the reason that he left was that he couldn’t get at the truth anymore? I’d like to keep that question in mind throughout our discussions. It might all be real; every serious moment and every wild moment equally. Or it might be a coping mechanism. Or it might just be the drug intake. You tell me.

One other thing any reader is bound to notice immediately is the world-building. Transmetropolitan has perhaps the most effortless and beautiful world-building I’ve seen in a comic. It’s balanced between the art and the text with hints scattered throughout the entire story about the state of the world, the City, the technology, and just about everything else. In the mountains, the tech is low. Spider has a curly-cord phone and not much else from the looks of things. He makes a comment about changing the channel on the TV in the bar. It has the initial appearance of being in our own time. The moment he arrives at the toll booth into the city, though, things begin to change. Various devices boot up, mostly news-related and talking about things like a secession movement on Mars. The toll-boy has a metal implant on his neck and says there’s no “navigation software.” Inside, the City is a wall of color, smells, noise, advertisements and people. Pages sixteen and seventeen give us a rundown of how diverse and strange the City populous is. Clearly this is not our world. It can’t be much far removed, thanks to the similar technologies and things like a “print district” where publishing still operates in roughly the normal pattern we’re used to, but all the same the City is a stranger to us. The home technology involves Makers, which can recombine matter from a base-block (for the rich) or trash (for the poor) to create food, clothes, etc. Then there’s the Transient movement and the mutated cigarette-smoking cat. The police gear and the cars are still our-kind-of-tech, though.

Without having to explicitly tell us, Ellis puts us in a narrative space-time continuum. It’s not too far in the future, but it’s far enough that the reader feels alien to the City and all of the developments humanity has made. Gene manipulation, Makers, holographic ads everywhere, sexual and cultural liberation, eating vat-grown people… Spider’s “laptop,” on the other hand, still has a typewriter style keyset. It’s a weird world.

Story-wise, “Back on the Street” is relatively simple. Spider is trying to find a way to make money to write the two books he owes while hooking himself back up to the City’s mad energy. That he happens upon Fred Christ’s picture on the television is coincidence but the ugly situation in Angels 8 allows for the more serious side of Spider’s personality to come into play. “The cops have their excuse. There won’t be a Transient left alive by sundown. I’m going to Angels 8. No, I do not have the faintest idea why, or what I’m going to do when I get there. The point is: I have to be there.” This is an important clue toward Spider’s attitude toward journalism, along with what he tells the dancers: “I can’t control anything with this typewriter. All this is, is a gun… It’s only got one bullet in it, but if you aim right, that’s all you need. Aim it right and you can blow a kneecap off the world.”

I’d like to believe that, too.

The Pictures

Much of the fantastic world-building is owed to Darick Robertson’s absolutely mindblowing art. I’m not shy about it; I love the art in Transmetropolitan. Every single inch of space contains some detail, some hidden secret. You can spend five minutes on every page studying the text in the backgrounds. The art makes the City real to us in a way the text alone couldn’t possible manage. It’s hard to pick just one thing to praise about the illustrations for Transmet but I’ll stick for now to the facial expressions, especially Spider’s. On pages 4-5 Spider visibly goes through a whole range of emotions from confusion to surprise to rage to sadness. The text doesn’t have to tell us any of that. Robertson’s attention to the creases and wrinkles of Spider’s face and the set of his mouth give us everything we need to know. (I actually miss Spider’s magnificent mane from the first issue sometimes; Robertson seemed to have so much fun drawing it.)

Not to mention the detail in Spider’s tattoos that show up in nearly every panel he’s in. His teeth are crooked, too. Robertson pays a huge amount of attention to the small things which help make the characters in Transmetropolitan real. In the final panel, Spider’s wounds and swollen face are ugly and believable. Without the art, there would be something missing from Transmetropolitan. It tells half of the story. Not all comics are like that, true, but this one is. It’s all in the details.

Pages 22-23 get my vote for favorite pages in volume one. It was a tie with the Cityscape panels where we start seeing the citizenry, but the sight of Spider getting the infamous glasses from the hopped-up Maker in nearly naked glory still makes me grin. (Plus, the crooked bottom teeth and slight gut make him look that much more real.) What’s your favorite scene?

Continuity?

There’s an amusing tiny plot hole in “Back on the Street.” Spider dumps his car in traffic during his return to the city and walks off over the tops of other people’s vehicles… But when he’s ready to go to the Transient riot in Angels 8, the same car is magically back. I wonder if the City kindly returns dumped cars? It seems much more likely that they impound them, but hey. You never know.

Come back next week for volume 2!

« Intro | Index | Vol 2: Lust for Life »

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.